A few months ago on the Dongfang Hour, we had reported that Chinese launch company iSpace had completed the definition phase of their medium-lift rocket, the Hyperbola-3, which was also an opportunity for them to reveal a few technical characteristics on the diA few months ago on the Dongfang Hour, we had reported that Chinese launch company iSpace had completed the definition phase of their medium-lift rocket, the Hyperbola-3, which was also an opportunity for them to reveal a few technical characteristics on the different versions. Among the different versions was an especially eye-catching one, the Hyperbola-3A, for its non-symmetrical structure (with only a single side booster!).

To review the several variants that were announced in June, before deep-diving into the asymmetrical rocket:

The Hyperbola 3 represent the upper end of the Hyperbola rocket family (larger than -1 and -2), providing different payload capacities thanks to 3 different configurations of the launch vehicle:

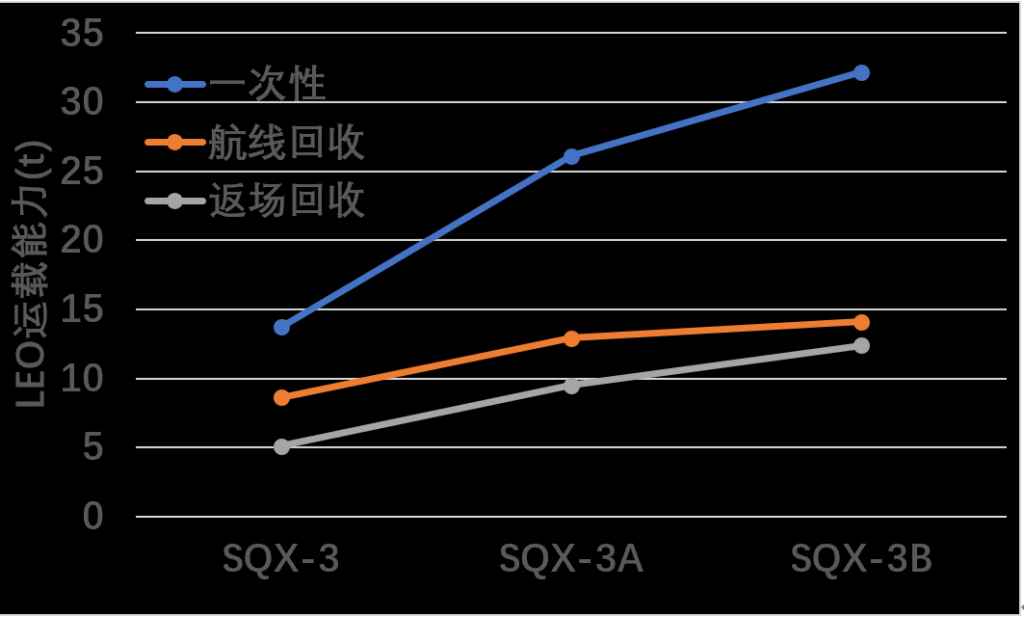

- The basic SQX-3, which is a two-stage version putting 13.6t into LEO (when expendable) or 8.6t in a reusable version (and landing in an area determined by a ballistic trajectory).

- The heavier SQX-3A, which a the SQX-3 but with an extra side booster, putting into LEO 26.1t (expendable)/12.9t (reusable). This is the standout, with an unusual non-symmetrical design. This likely makes the stability of the rocket much more complex, and with a center a gravity deported towards the single booster. I think this is unprecedented in rocket design.

- The heaviest SQX-3B, sort of a “Falcon Heavy” version of the SQX-3 with 2 side boosters. This rocket puts the 32.2t into LEO (expendable version) and 14.1t (when reused).

A Modular Architecture

About a month later in July 2021, iSpace provided some further insights on their decision behind this unusual rocket layout, namely:

- First, iSpace mentions that while the architecture of this rocket seems bizarre, it is not the first such design. The American Space Shuttle was famously a great example of a non symmetrical design, with the orbital vehicle (spaceplane) hanging to one side. Similarly, the Soviet Union’s Buran spaceplane hung to the side of the Energia rocket, to a similar effect.

Another famous and perhaps less obvious non-symmetrical rocket is ULA’s Atlas V, which can accept 0, 1, 2, 3 and 5 side boosters. Every version except the one without side boosters is non-symmetrical, and this is obvious when looking at the rocket from above. And notably the version with a single side booster, called the 411 version of the Atlas V, looks similar to the Hyperbola 3A. - The major disadvantage of such a layout is that the offset of the booster from the center of gravity creates torque, which in turn needs to be compensated by some significant gimballing from the first stage engines. This means basically orienting the engine nozzles in a direction different from the main axis of the rocket to create torque in the opposite direction. Another solution proposed by iSpace would be to apply variable thrust to the many engines of the first stage, creating torque in the opposite direction.

- Another tricky part according to iSpace is that the flight dynamics laws are significantly more complex than for axisymmetric rockets. This is quite understandable, symmetry being a classical source of simplifications in equations.

Not impossible to do as the US and soviet programs have proven, but just an additional finicky balance to get right.

Which brings us to the question: why do this at all?

iSpace mentions that the asymmetrical rocket is to have a more versatile Hyperbola 3 family. The Hyperbola 3 with no side boosters has a 13.7t payload capacity into LEO when expendable, and the Hyperbola 3B with 2 side boosters has this capacity increased to a whooping 32.2t. The Hyperbola 3A sits in-between them at 26.1t. Similarly in a reusable version, we get 8.6t, 12.9t, and 14.1t into LEO.

Definitely a more versatile payload capacity to offer to customers, and with minimal development time and costs due to the modular approach, according to iSpace.

If iSpace actually pursues this solution (remember, we are still at a very early stage) and is successful, it will be a clear demonstration that Chinese commercial launch companies are also able to innovate, rather than just “copy” SpaceX technical solutions. And in the meantime, we have further validation that iSpace is one of China’s most innovative, leading commercial launch companies.