China is a country known for its every five-year publications. The most famous is the National-level Five-Year Plan, an all-singing, all-dancing, couple hundred page document that gets published every ~60 months with detailed instructions on the development path of the Middle Kingdom moving forward. Recent National-Level Five-Year Plans have included some nuggets on space, but inevitably these tend to be one or two lines in a document with tens of thousands of them.

That being the case, those of us watching China’s Space Sector have a different five-yearly paper to look forward to, namely China’s White Paper on Space, published by the State Council and including detailed accomplishments from the previous five year, major tasks for the upcoming five years, supporting regulations and policies that will help complete these tasks, and finally, a section on international relations in the space domain.

This half-decade’s White Paper was published on 28 January (full English, and Chinese versions here), and included a long list of notables. If the paper is any indication, the next five years will see China’s space sector become more commercialized, more international, and more integrated with the rest of the economy, and in particular, the rest of China’s digital infrastructure. Ambitious missions will be undertaken, and cutting-edge technologies will be developed, supported by a trifecta of Government, SOEs, and private venture capital. In short, it’s been a very impressive 5 years to 2021 in Chinese space, but incredibly, we might just be getting started.

China’s 2021 Space White Paper: An Overview

The 2021 edition of China’s Space White Paper follows a broadly similar structure to previous editions, but with some notable differences. There is a less clear delineation between accomplishments of the past 5 years, and plans for the next 5 years, and the tone from the get-go is one of a country that is striving for space leadership, or at a minimum complete autonomy.

The first, and perhaps most apparent difference, however, is the very first paragraph of the White Paper. Let us compare 2016’s with 2021s:

2016: Aerospace is one of the most challenging and widely driving high-tech fields in the world today. Space activities have profoundly changed human’s understanding of the universe and provided an important driving force for the progress of human society. At present, more and more countries, including developing countries, take the development of spaceflight as an important strategic choice, and the world spaceflight activities are showing a booming scene.

2021: “To explore the vast cosmos, develop the space industry and build China into a space power is our eternal dream,” stated President Xi Jinping. The space industry is a critical element of the overall national strategy, and China upholds the principle of exploration and utilization of outer space for peaceful purposes.

So, if we compare the 2021 White Paper with all the previous White Papers, this one is winning in the “Quotations from Xi Jinping” category, 1-0, after sentence #1 of the paper. For better or worse, the times in China are a’changin’.

Digging into some of the more space-related details of the White Paper, we see quite a few interesting takes. First, the White Paper makes it clear that the space sector is seen as a growing industry in the context of China’s economy. On pg. 1 of the White Paper, the authors note that “The space industry will contribute more to China’s growth as a whole”, while calling for more innovation and efficiency in the development of new space technologies.

A growing space sector requires more companies, and in the Chinese context, a lot of these new companies are commercial companies, putting them on the outside of the state-owned apparatus. Historically, we have seen commercial companies operating in a completely different universe from their state-owned counterparts, with the analogy of the casino and the card counter coming to mind (SOEs are the casino: they are the house and they always win. Commercial companies are the card counter: they need to wait until the card count (regulatory environment) gets good, make their moves fast, and get the heck out of there).

But this year, we saw something different–the 2021 White Paper actually mentioned commercial companies (or at least their products) by name. When discussing the success of China’s launch vehicle development over the past several years, the article mentions the Hyperbola-1 and Ceres-1 rockets from iSpace and Galactic Energy, respectively, with these two rockets having successfully debuted in 2019 and 2020, respectively. This seems to be a continuation of a trend we’ve been seeing for 1-2 years now, namely that the State and state-owned apparatus are treating commercial companies with more respect.

In the early days of Chinese commercial space (i.e. like 5 years ago), SOEs and the State more generally viewed commercial space companies as totally insignificant. More recently, as commercial companies have gotten bigger, richer, and more technologically advanced, the traditional players have changed their tune. The first major instance of this (AFAIK) would have been China Space Day 2021 in April, when China Rocket–a commercial subsidiary of CASC–gave a speech in which they spoke about commercial constellations as an important source of demand for China Rocket. This was a validation of commercial companies, and to some extent an admission by the SOEs that they may have judged the commercial companies too soon–these guys are serious, and heck, they might end up being good customers for the traditional companies.

Taking us all the way back to the White Paper, point being, more commercial involvement should be expected moving forward. We even saw in the White Paper mention of a commercial launch pad being built at Jiuquan during the coming 5 years, a clear effort to improve launch site access for commercial companies.

Major Projects and Initiatives

We’ve seen that the next 5 years in China’s space sector will apparently involve more commercial companies, and may also involve more direct involvement by the highest levels of power of the Communist Party. That being the case, what type of stuff is China planning to do in the next 5 years under this new paradigm? Quite a lot, with the White Paper calling for:

- Next-generation manned carrier rockets (LM-5DY probably)

- More integration of satellite communications, navigation, and EO networks (i.e. 通导遥一体化)

- Build a LEO/GEO satellite communications network, as well as a second-generation data relay satellite system

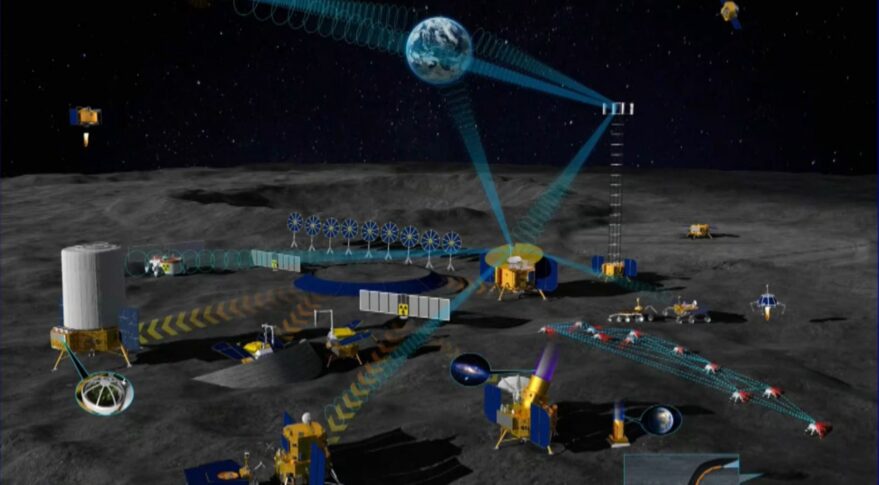

- Continue studies on human lunar landing, including making progress on the ILRS

- A variety of space science missions, including telescope and probes

In addition to a number of concrete goals such as the ones listed above, the White Paper saw some intriguing soft goals, such as:

- Strengthening unified technical standards for China’s space products

- Strengthen space traffic control

- Study plans for building a near-earth object defense system

- Modernizing space governance, with multiple mentions of the United Nations and its “central role…in managing outer space affairs”

In short, not only a very ambitious list of projects, but also a very ambitious list of how China seeks to define international relations, dispute resolution, and governance in space. Moving forward, as we launch thousands of satellites and hundreds of rockets per year, these topics are going to become increasingly important, and it seems that China understands this, and is positioning itself to protect its self-interests in the space domain.

International Cooperation in the Space Domain

One concept that was made abundantly clear in the White Paper is the importance of international relations to China’s space program. A few lines stood out in particular. First, the highly specific point that China will give priority to developing communications satellites for Pakistan, and to cooperating on the construction of the Pakistan Space Center and Egypt’s Space City.

It is not surprising that these two countries gain special mention. Pakistan is one of China’s most important allies, a country of >200M people with a shared border, and perhaps more importantly, a longtime rivalry with China’s eternal rival, India. Egypt is the most populous country in the Middle East, and happens to straddle one of the world’s most important shipping lanes, the Suez Canal. In short, both countries are very important to China’s security and economic interests, and it seems China is giving priority to projects in these countries.

Other international cooperation includes wider international distribution of Chinese EO satellite data, including a BRICS EO satellite constellation planned for the next 5 years, more personnel exchanges and international academic conferences, and sharing data from lunar missions such as Chang’e-4 with the international community, in this case via UNOOSA. Finally, the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), a joint project with Russia, is also clearly open for business, with the White Paper noting that the ILRS “welcomes international partners to participate in the research and constriction of the station at any stage and level of the mission“.

Conclusions: What to Make of the 2021 White Paper?

China’s 2021 Space White Paper takes on a markedly different tone than previous editions. With larger ambitions, more emphasis on commercial involvement and innovation, and a clearer vision of how space can impact the broader economy, the 2021 edition may end up being the beginning of the widespread adoption of commercial space in China.

In terms of regulatory developments, this year saw China take a more assertive tone, making it clear that space is an international commons and putting a lot of support behind UNOOSA, and moving forward we are likely to see China take a more active role in global space governance.

Clearly, the next 5 years in the Chinese space sector are going to be very eventful. With bigger missions, more international collaboration, and a wider variety of Chinese commercial companies playing a larger role in the development of the sector, we should expect to see rapid evolution, more money spent supporting commercial space firms, and more international efforts undertaken.

The space sector is changing quickly all around the world, in a number of ways. If the 2021 Chinese Space White Paper is any indication, the next several years will see a broad change in the global space sector becoming somewhat more Chinese.