A Decentralized System?

One very common stereotype about China is that it is highly centralized. While true to some extent, it is de facto highly decentralized: provinces enjoy a relatively large margin of maneuver in applying policies defined at the national level. It is also the case when it comes to space policies, and the following analysis of China’s provincial space policies, based on a very comprehensive article published by Satellite World (卫星界), can tangentially illustrate it.

Provincial space policies: an overview

The article identifies 24 provincial and municipal space-related policies, issued by 14 Chinese provinces/cities, either in 2020 or 2021 (except for one policy by Fujian Province, from 2018).

Several of the policies are admittedly only tangentially related to space, or otherwise are much broader policies that have some relatively small space component. For example, in March 2021, Ningxia apparently passed a “2021-2023 Plan to Build Digital Governance”, which included, among other things, accelerating the development of GIS systems, integrating BeiDou with Gaofen EO satellites, and increasing data collection. Yet, given the recurrence of the term ‘satellite’ (27 times), the selection seems to be relevant to our topic.

Overall, there is a major emphasis on ‘New Infrastructures’ (新基建), which is not surprising given that the NDRC New Infrastructure White Book was published in April 2020 – i.e., prior to most of the present policies. New infrastructures include mainly 5G, big data, artificial intelligence, industrial Internet, and Internet of Things (IoT). It aims at enhancing connectivity across China and at developing smart cities. All the provinces and cities that are mentioned in the article have issued at least one satellite-related policy in the past ~18 months. More specifically, the development of satellite applications is a goal of 7 policies; satellite internet is mentioned by 3 provinces, including Shanghai, Sichuan and Fujian.

Among the specific satellite applications, remote sensing, satellite navigation, EO, data collection, and digitization of everything are the most popular ones. Strong emphasis is put on the development of the Beidou industrial base and the development of Beidou applications. As far as EO is concerned, the focus is on environmental protection and monitoring – we can only imagine that such a trend will increase, given the major flood in Henan this summer. The Guangdong Province even included the development of an AI-powered robot, equipped with an intelligent warning system, which would monitor meteorological conditions in the South China Sea from space.

What role will these provincial policies actually play?

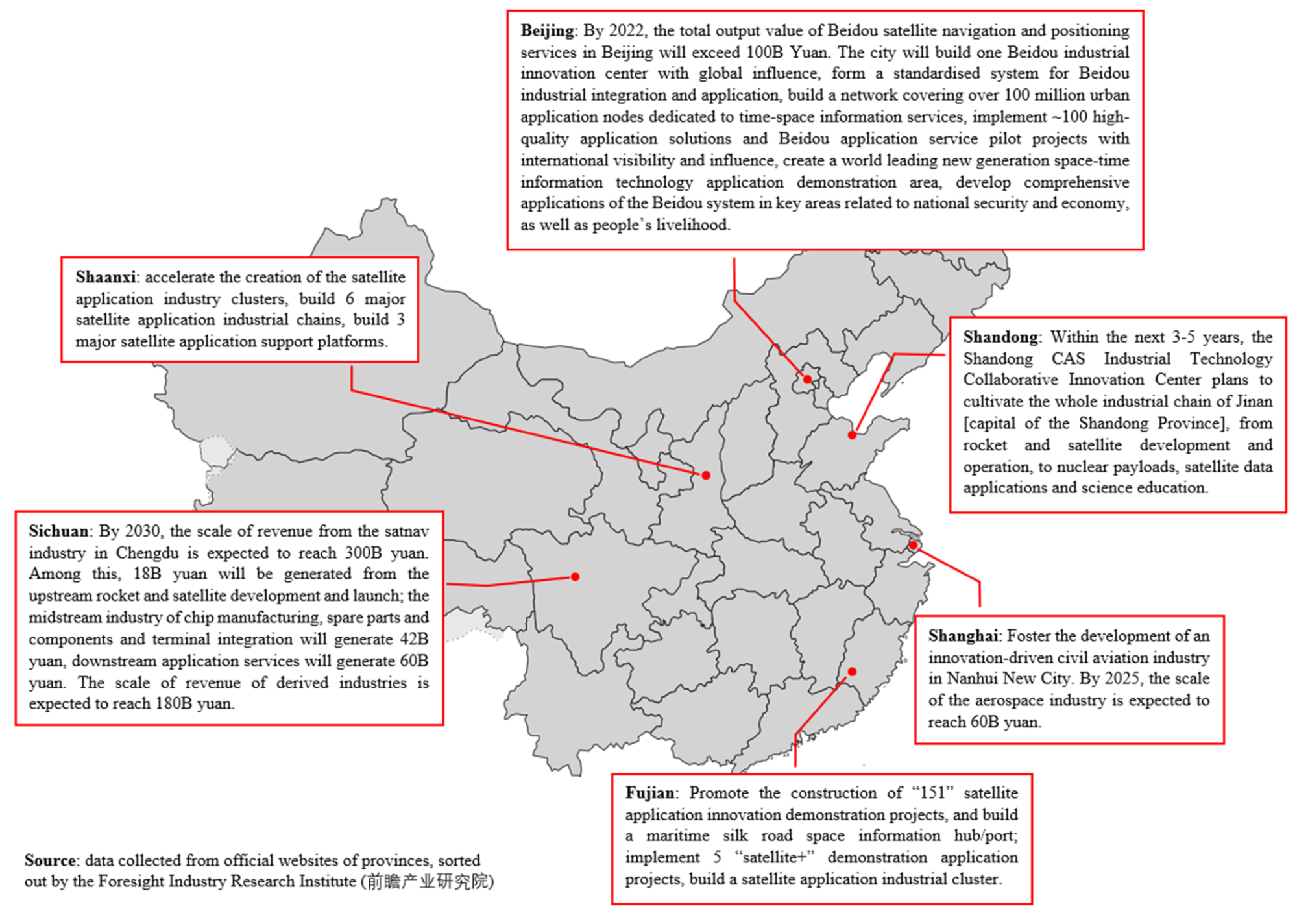

Interestingly, a number of provinces have included a number of concrete development goals to be reached within the coming few years or decade. Below is the translation of the map included in the article.

As we have discussed at length on the Dongfang Hour, the Chinese development model has its benefits and drawbacks, and all these regional development plans highlight both. On the one hand, there are a lot of resources being poured into highly strategic industries, by entities that have the ability to “move the needle” in terms of development. On the other hand, several of the initiatives look pretty similar to one another, and the sheer number of initiatives indicates some level of potential inefficiency, or at a minimum overlap.

Moving forward, we can probably be sure of two things. 1) China’s space sector is going to continue developing at both a national and provincial/city level, propelled in part by government initiatives, and 2) there may be some underutilized space assets in the medium-long term as many, many provinces and cities subsidize space sector development.