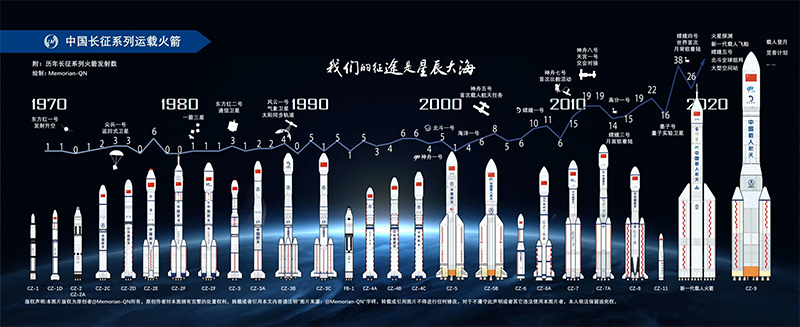

Since the 2010s, China has been putting into service a new generation of Long March rockets, based on new engine designs, cleaner fuels (kerosene, hydrogen), and with higher specific impulse. The Long March 6 (light lift) made its maiden flight in 2015, the Long March 7 (medium-heavy lift) and 5 (heavy-lift) were launched in 2016, and more recently the Long March 8 (medium lift) in 2020. Several variants have also seen the day, notably the Long March 7A (additional 3rd stage), and the Long March 5B (optimized for LEO).

These rockets, which mostly launch from the Wenchang launch center in Hainan province, have a double advantage compared to the older Long March 2-4. The more recent engine technology enables higher efficiency and avoids manipulating highly toxic fuels such as UDMH (unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine), a legacy of China’s old practice of deriving missile technologies for civil launch vehicles. The new rockets* also launch from a coastal site, a clear advantage over the Long March 2-4 which do so from the land-locked sites of Jiuquan, Taiyuan, and Xichang, where first stages tend to come back down on potentially inhabited areas.

*except the Long March 6

To enable the development of these new Long March rockets, China has naturally developed over the past decade a new set of engines: the YF-100 (kerolox), the YF-115 (2nd stage, kerolox), YF-77 (2nd stage, hydrolox). Further improvements have also recently been brought to these designs, such as the YF-100K.

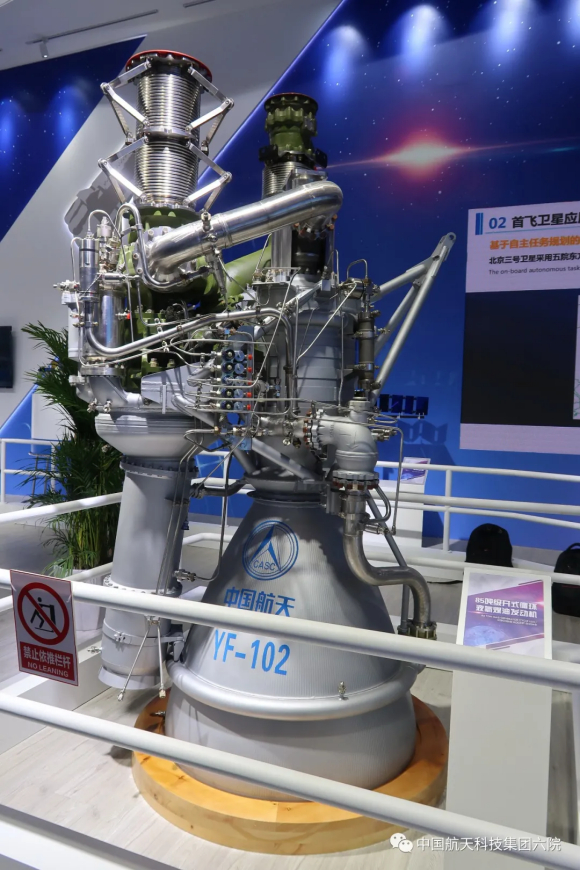

In Comes the YF-102 Engine

It is clear today that the Long March 5 to 8 are well-furnished in terms of propulsion, and that there is no particular need in this regard. But then in came the YF-102, an engine that was unveiled for the first time at the 2021 Zhuhai Airshow.

According to various videos from the manufacturer Academy of Aerospace Propulsion Technology (AALPT), The YF-102 is a 85t thrust-class expander open cycle (开始循环发动机). It burns kerosene and liquid oxygen, and its thrust at sea level can vary between 620 kN and 835 kN. As mentioned by some of the marketing material made available, the engine benefited from China’s previous experience in developing kerolox engines.

According to AALPT, the YF-102 is in the final stages of testing, with 6 fully assembled engines having already performed test fires and some that have lasted up to 200 seconds. The engine could be operational by 2022, and the company is also talking about a reusable version of the engine, the YF-102R, ready by 2026.

Who is actually going to use this engine?

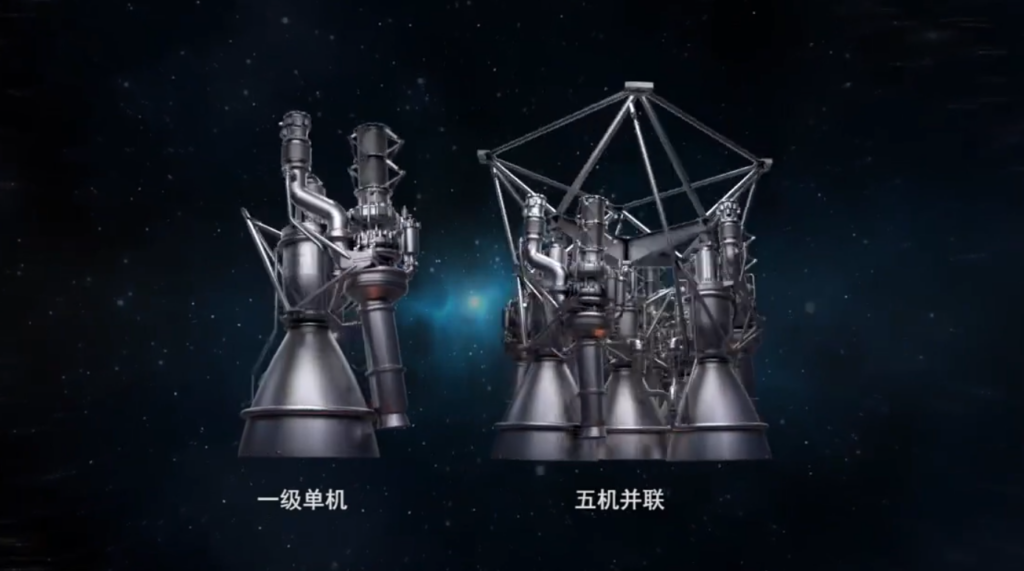

The million-dollar question is: which Chinese rocket will actually use this engine? As discussed earlier in the article, the current new generation Long March rockets are already well equipped with the YF100-family of rocket engines and have no use for the YF-102.

A clue could be in the more “commercial space” pitch of AAPLT’s presentation. The CASC subsidiary puts forward the simple design of the engine, the optimizations in manufacturing and maintenance, and the use of 3D printing to bring the cost of the engine down. The engines will also be able to restart multiple times, an indispensable feature for reusability. This tends to suggest that a “commercial” Chinese launch provider could make use of such an engine. Several photos and video animations showed also 5-engine and 9-engine clusters which are not without reminding the viewer of a Falcon 9 first stage.

Looking into the potential buyers of the YF-102 , several candidates are possible:

- China Rocket (中国火箭): a commercial spin-off of the Chinese Academy of Launch Technology (CALT), China Rocket is “the most state-owned” commercial launch company, and would deserve the use of quotation marks around the word “commercial”. The company is currently designing the Jielong series of solid-fueled rockets, and had also previously announced in 2019 a plan develop the Tenglong series of commercial liquid-fueled rockets.

- Expace (航天科工火箭): a commercial launch spin-off of competing State-owned entreprise CASIC, Expace is less likely to use anything from CASC-affiliated academies. Nevertheless CASC and CASIC have already collaborated multiple times on various Chinese space program missions, and Expace has been hinting lately at the development of a series of liquid-fueled rockets (the Kuaizhou-2).

- Commercial/private launch companies: Chinese commercial launch companies, most of which have been founded in recent years with the opening up of the Chinese space sector, could also benefit from this engine. Among these companies, most first-generation players have developed their own medium-lift rocket engines, such as iSpace (Jiaodian-2), Landspace (Tianque-12) and Galactic Energy (Cangqiong). However, many more recent newcomers such as Ospace (a.k.a Orienspace) or SpacePi may not have the time to do these developments internally, and could be interested in buying engines from an external provider.

Worth noting, launch companies that would want to outsource engines will have several options beyond the YF-102. There are several Chinese startups specialized in rocket propulsion, such as Aerospace Propulsion or JZYJ. - International markets: could the YF-102 work as an export product? The engine is probably to a very large extent Chinese-developed, with no specific export restrictions. Non-Chinese (and probably non-Western) companies could be interested in the YF-102 if it is price-competitive. However the ability for CASC to tap into such markets remains to be seen.

Admittedly, a lot of the possibilities mentioned above are speculation. With a first flight-ready YF-102 delivery planned for late 2022, and a reusable version in 2026, space watchers around the world will likely have to wait another year or so to see how YF-102 commercial perspectives develop.