2021 was arguably the biggest year for space in decades, with dozens of humans launched into orbit, multiple missions reaching the Moon and Mars, and a variety of constellations being deployed into low earth orbit. These accomplishments were done by governments and companies from all over the world, but China (along with the United States) stood out in terms of the breadth of its programs, and the variety of accomplishments and major events in 2021.

Despite two years of Covid-19, closed borders, constantly-changing policies, and a plethora of other roadblocks, the space sector has seen a stellar decade thus far, and this year the foundation was laid for even more impressive achievements to come. At Dongfang Hour, we’ve been lucky enough to cover the Chinese space sector all year, where over the course of 52 weeks, we’ve covered >600 news stories in our newsletters, YouTube videos, and other media. While it would be impossible to narrow it down to merely the “Top 8”, or even to define what “Top” might mean, we thought it would be fun to pick 8 trends or events from 2021 that were notable, interesting, or otherwise significant. The list is rather long, so we’ve broken it into two articles–this one covers #1-4.

The trends include a couple of space exploration topics (ILRS Lunar base, Tianwen Mars Mission, Chinese Space Station), launch updates (An amazing year, some new launch infrastructure, and the rise of Chinese space tourism), and satellite constellations (both comms and EO). Some high-level themes also included international cooperation, technology development, and space as a strategically important sector, with these themes appearing across several topics.

1. Going to the Moon with Russia: the kick-off of the ILRS

China’s announcement with Russia of the ILRS project (International Lunar Research Station) was one of the highlights of 2021. Arguably China & and Russia’s equivalent of the Artemis program, ILRS would take place over the next 15-20 years in 3 phases: Reconnaissance, Construction and Utilization. This project includes ambitious goals such as lunar resources mining, in-situ resources utilization, energy harvesting, and most ambitiously: enabling Chinese and Russian astronauts to set foot on the Moon sometime in the 2030s.

Perhaps more interestingly from a geopolitical point of view, China and Russia, through this project, are offering to countries an alternative to the US-led Artemis program, the other very ambitious lunar exploration program, which has a head start of a couple of years. ILRS’s offer is in some ways a convincing one, with the strong funding coming from China, its recent high profile successes such as Chang’e 5 and Tianwen-1, and Russia’s decades-long experience in space technology.

Of course, a big question is will China and Russia manage to convince other countries to join the ILRS, especially with China having a track-record of essentially national programs, although there have been some significant bilateral collaborations. On the other hand, Italy, Australia, the UK, Japan, South Korea, Brazil, New Zealand, Poland, the UAE, Ukraine, and more recently Mexico have all signed the Artemis Accords. It will be interesting to watch if and who China/Russia will be able to attract. Recent rumors have suggested interest from France, Italy, Saudi Arabia and Thailand.

Note: check out our infographic comparing Artemis and the ILRS.

2. China becomes the 2nd country to ever (successfully) land a rover on Mars

In parallel to these preparations and announcements for future lunar activity, history was being made on Mars in 2021. Three historic missions, NASA’s Mars 2020, UAE’s Hope, and China’s Tianwen-1 Mars made it to Mars early in 2021. The Tianwen-1 mission is composed of an orbiter, a lander and a rover named Zhurong. The orbiter successfully reached Mars in February 2021 after a 6-month trip. After a reconnaissance phase of a couple of months during which the spacecraft remained in orbit around Mars, the orbiter released the lander carrying the Zhurong rover on May 15. The lander entered the Martian atmosphere successfully, successively braking aerodynamically, deploying supersonic parachutes, and using retropropulsion to touchdown softly. And ever since, the Zhurong rover has been roaming the Martian ground in the region of Utopia Planitia, and had driven 1253m by November 8 2021.

This mission is historical for China for many reasons. It’s China’s first fully independent deep space mission (beyond Earth’s and Lunar orbit). It also makes China the second nation to successfully land a rover on Mars after the US, with European countries and Russia having failed this in the past for various technical reasons. The breadth of the mission is also impressive: as the Chinese often like to say, Tianwen-1 accomplished putting an orbiter around Mars, landing a lander, and a rover all in one mission, something that was done through separate missions by other space-faring nations (this can be attributed to latecomer advantage). Ultimately, it symbolizes China’s transition from a catch-up phase in space exploration, to a phase where it is attempting things that have not been done before, with its next missions (a Mars sample return, permanent base on the Moon). The next decade is going to be absolutely fascinating to watch for space exploration, with an unprecedented number of ambitious projects.

3. Guowang and Plans for Mass Smallsat Manufacturing

April saw the creation of China Satellite Networks Limited, or 中国卫星网络集团, a state-owned enterprise that will deploy China’s answer to Starlink and other megaconstellations. A formal announcement on constellation size has not been made yet, but ITU filings from late 2020 suggest >10,000 satellites.

The creation of China SatNet gives China a centralized and high-level organization that is also seemingly independent of CASC, CASIC, and other incumbents. As such, China SatNet can (in theory) procure satellites, rockets, and other equipment from a variety of suppliers, including CASC, CASIC, and maybe, commercial companies. HQed in Xiong’an, the planned city South of Beijing, the company also appears to be very close to the central government. No formal timeline has been laid out for the deployment of Guowang, but we assume that 2022 will begin to see test satellites launched–indeed, 2021 may have already seen that, with a couple of mysterious “Low Earth Orbit Broadband 5G Test Satellites” launched in August of this year.

In December, we saw a meeting between China SatNet and the government of Chongqing City, where the most noteworthy statement was from China SatNet Chairman Yang Baohua, who stated during the ceremony that:

“the construction of a national satellite internet system, and the establishment of China Satellite Network Limited, are major strategic decisions made by General Secretary Xi Jinping and the Party Central Committee”.

China SatNet Chairman Yang Baohua

If we are to take Yang’s word for it, then China SatNet and the Guowang constellation are such strategically important projects that they were called for by President Xi himself. This would be good news for the development of SatNet, in that it has very high-level support.

In terms of hard infrastructure being developed for satellite constellations, 2021 also saw multiple companies advance their satellite manufacturing efforts, including Galaxy Space, GeeSpace, Commsat, and others. Surprisingly (given the number of launch startups in China), a major bottleneck for several batches of comms satellites has been launch vehicles, with most national launches being spoken for, and most commercial companies not yet launching regularly. Moving forward, we may see a rapid acceleration in deployment once China’s commercial launch cadence picks up.

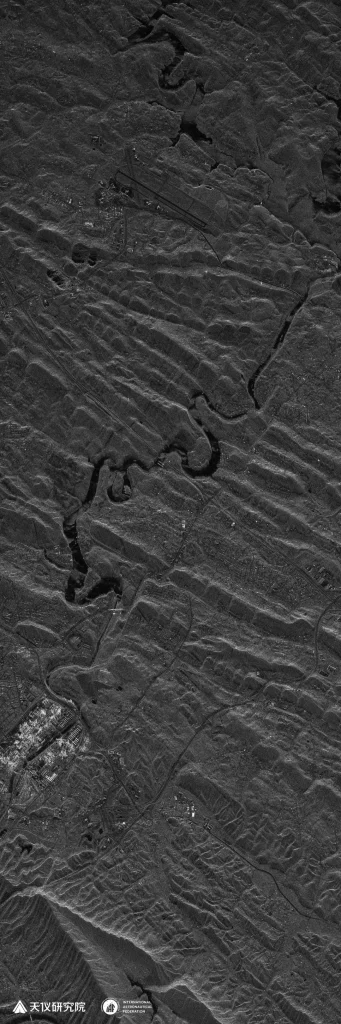

4. SAR Goes Mainstream

The end of 2020 saw the launch of China’s first C-band SAR satellite, Haisi-1, to be operated by CETC 38th Institute and Spacety. The timing ended up being perfect, with early 2021 seeing the M/S Ever Given, a container ship, get stuck in the Suez Canal, much to the dismay of its owners, but much to the benefit of a variety of EO satellite operators, including CETC38 and Spacety, with dozens of images of the ship captured by these various satellites.

Later in the year, we saw SAR satellites play a big role in capturing and transmitting critical data during the flooding in Zhengzhou, Henan Province, which significantly raised the profile of satellites such as Gaofen-3.

As the year went on, we saw SAR become one of the hottest topics in Chinese space. Among the SAR projects announced during 2021 was the 96-satellite Tianxian constellation, to be developed by Spacety and the CETC38. The ambitious constellation is being led/likely bankrolled by CETC38, one of China’s leading companies in terms of SAR technology, and a large subsidiary of the China Electronics Technology Corporation.

2021 also saw a 4-satellite SAR constellation announced by EO data analytics company PIESat. The announcement, made in late August, was well-received by Chinese financial markets, with PIESat’s valuation increasing by ~40% over the rest of the year, to slightly more than RMB 13B (~US$2B) as of 24 December. The end of 2020 saw a Silk Road SAR constellation announced, to be developed by Smart Satellite and Tongchuan City, Shaanxi Province. We also saw the two Tianhui-2 satellites, developed by the CETC 14th Institute, in August 2021, with these satellites using SAR technology for 3D topographic mapping.

Around 20 provinces also included specific support for remote sensing in their provincial-level five-year plans, published in 2021. Most of these were focused on application-level support, i.e. making use of remote sensing data for things like city planning, agriculture, disaster relief, etc., and are likely to benefit the large number of provincial-level data analytics companies in the EO segment. A smaller number of provinces have announced plans for their own (usually small) constellations.

Stay tuned for Part 2, to be published early next week!