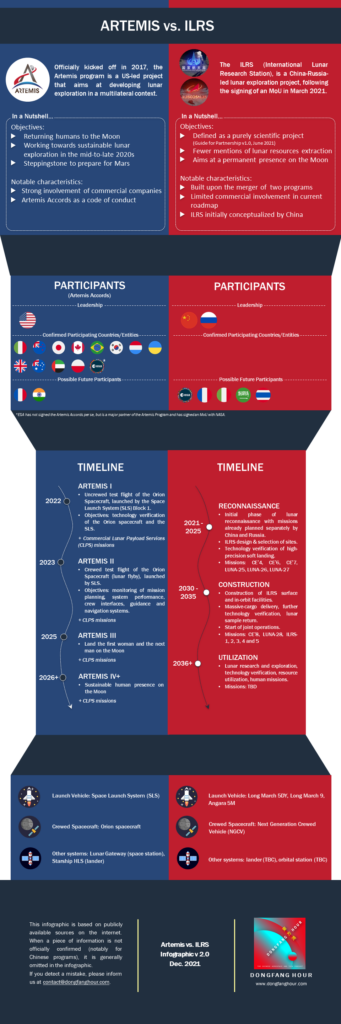

It is no secret that China and the United States are engaged in a great power competition that is extending to the space realm. The Artemis Program and the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project constitute a tangible example of such competition. After an overview of both projects, this article offers a comparison of the key dimensions, analyzing the future of lunar exploration in a contested environment.

Both projects share similar, potentially competing ambitions

Artemis Program: a relatively well-defined project with tangible advancement

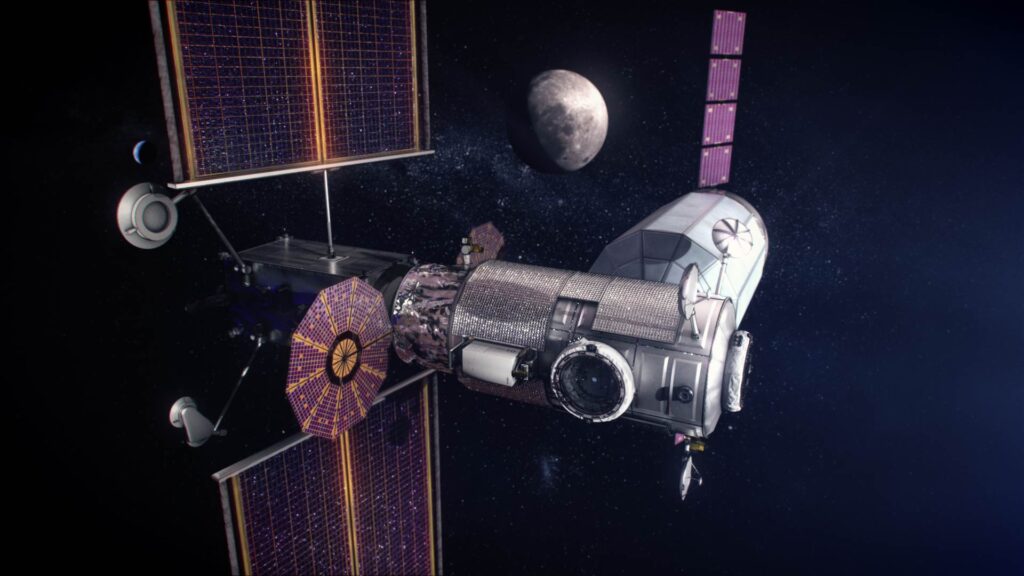

The Artemis Program is the US NASA-led lunar exploration program aiming at landing “the first woman and next man on the Moon by 2024” and at establishing a sustainable human presence on and in orbit around the Moon. To fulfill such objectives, NASA plans to build both a lunar lander (to be developed by SpaceX), a lunar base (aka the Artemis Base Camp), a lunar orbiter (the Lunar Gateway), and has wrapped up the design of the spacecraft that will send astronauts to the Moon (the Orion spacecraft).

International partners are expected to play a key role in the carrying out of the Artemis Program. NASA has indeed already secured cooperation with several international space agencies to build the Lunar Gateway. The Canadian Space Agency (CSA) will supply the robotic arm (canadarm3); the European Space Agency (ESA) will provide the International Habitat (I–Hab) module as well as the European System Providing Refueling, Infrastructure and Telecommunications (ESPRIT) module, lastly, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) will contribute “habitation components and logistics resupply”. ESA will also contribute a service module to the Orion spacecraft (agreement made back in January 2013).

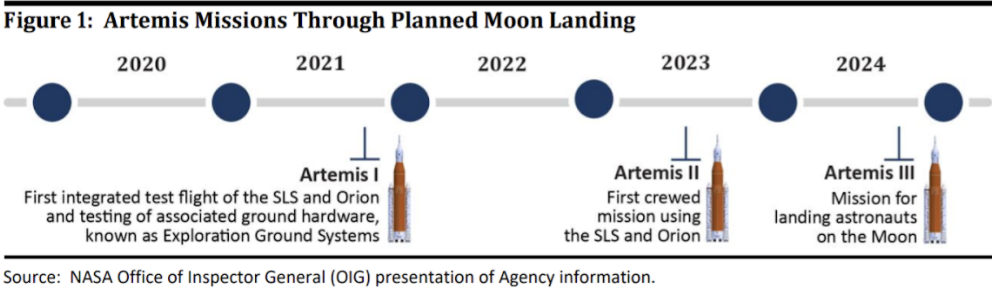

The Artemis program currently consists of four phases: Artemis I, II, III, and IV. Artemis I consists of the uncrewed test flight of the Orion Spacecraft, launched by the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket. It will take place sometime in 2022, though it was originally planned to be launched in 2020. Artemis II plans for the crewed test flight of the Orion Spacecraft by 2023, launched by the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket. Lastly, the goal of Artemis III is to land the first woman and the next man on the Moon. The date of launch of this third mission has recently been pushed back to 2025, after the initial date (2024) was deemed overly ambitious by several players. The Artemis IV mission will follow in 2026, with the first flight of the SLS Block 1B, and will also send the I-Hab module to the Lunar Gateway.

While those missions provide a concrete blueprint regarding how to reach the Moon, subsequent ones (Artemis V and beyond) will determine how a sustainable human presence will be established on the lunar surface. The Artemis Accords already outline the shape that international cooperation for the scientific exploration and commercial exploitation of the Moon will take in the near future through a series of bilateral framework agreements.

As of October 26, 2021, 13 countries are signatories of the Accords, including Brazil, Canada, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Ukraine, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the United States. Lastly, it is important to note that the Moon is a “stepping stone for our next greatest leap—human exploration of Mars”.

ILRS: a roadmap for international scientific cooperation on the Moon

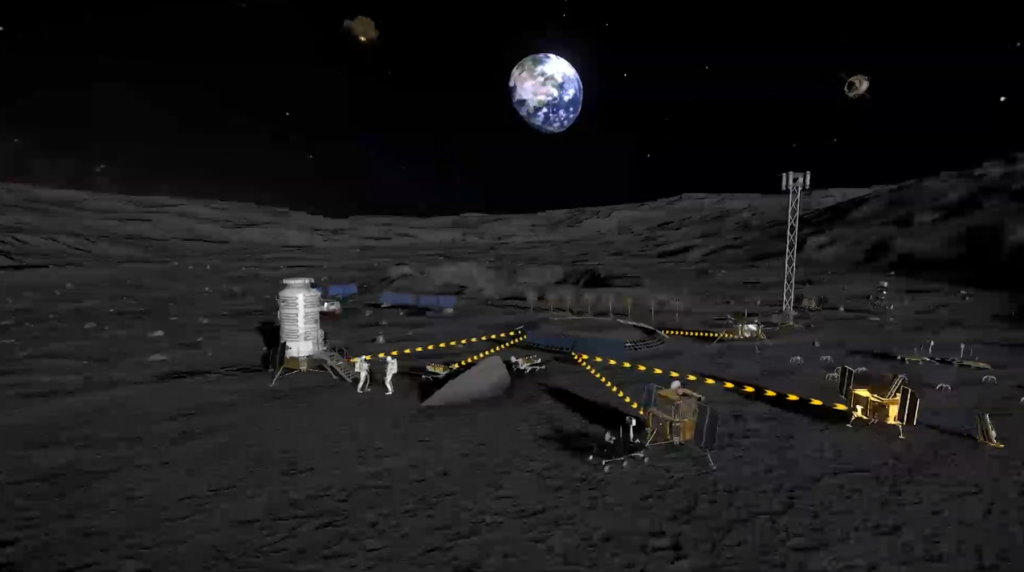

While the Artemis Program is well defined and already well underway, the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project is relatively early-stage in comparison – yet no less ambitious. First initiated by China, the project is now jointly conducted by China and Russia since the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the two countries in March 2021. A roadmap was released in June, outlining the steps towards the building of “experimental research facilities to be constructed with a possible attraction of partners on the surface and/or in the orbit of the Moon… with the prospect of subsequent human presence.”

The ILRS project is divided into three phases: a 1st phase of Reconnaissance (2021-2025), which aims at the verification of key landing technologies as well as the selection of a suitable site for the subsequent establishment of the ILRS; a 2nd phase of Construction of ILRS surface and in-orbit facilities following massive-cargo delivery, with further technology verification, to be conducted from 2030 to 2035; a 3rd phase of Utilization of the ILRS facilities for the conduct of scientific research and exploration, as well as for the conduct of crewed missions. This last phase is planned to be conducted from 2036 onwards and also involves technology verification. Each phase is open to the participation of international partners. Although no official partnership has been announced yet, France and ESA, among others, are mulling participation with China and Russia.

Comparison of key characteristics of both projects

Objectives: while the end objectives of both projects are similar – scientific exploration of the Moon and exploitation of lunar resources -, the ILRS project does not explicitly outline a plan to establish human presence on the Moon (it only mentions the “prospect for subsequent human presence”) and does not plan for subsequent Martian exploration. Furthermore, the ILRS project seems to focus more on scientific exploration, compared to the Artemis Program which seems to focus more on commercial exploitation (this may be speculative).

International partnerships: international cooperation is at the heart of both projects. Yet, while NASA has already secured multiple international partnerships in the framework of the Artemis Program, for the time being, China and Russia have not found partners willing to collaborate on the ILRS project (likely due to the fact that the ILRS framework was set up only very recently).

Concentration of leadership, i.e. how much power do the leaders (US/China + Russia) have, compared to partners:

The Artemis Program seems to be very much US-led and US-focused. Indeed, although international partners play a key role in the implementation of the missions, the direction of the project was unilaterally thought out and designed at the outset by the US. The Artemis Accords provide an illustration of such unilateralism: as a series of bilateral agreements drafted by NASA/US Department of State, the leadership is undoubtedly on the US side, with the content of the Accords seemingly not open to discussion.

As far as the ILRS project is concerned, China and Russia seem to share equal leadership. It is difficult to predict what international cooperation will look like for the time being, and indeed, given that China’s space program remains in ascendance, while Russia’s is stagnant if not in secular decline, we may yet see China take a more assertive leadership role in the ILRS than has thus far been indicated.

For both the Artemis Program and the ILRS project, the level of concentration of leadership during the phase of scientific exploration and exploitation of lunar resources is hard to predict.

Level of detail: while both projects remain, well, projects, the Artemis Program seems to provide a much better-defined action plan towards building a lunar orbiter and reaching the Moon, including key milestones to be reached at specific dates, and its implementation is already underway. The ILRS roadmap does provide detail on key missions to be led in each phase, yet action steps to be taken for each of the missions are less clearly defined.

Budget: As no figure has been released for the ILRS project, it is difficult to make a relevant comparison. As far as the Artemis Program is concerned, its implementation from 2020 to 2025 will cost a total of US$86 billion according to estimations by NASA’s Office of the Inspector General.

The future of lunar exploration and exploitation in a contested environment

Given the similarities between the Artemis Program and the ILRS project, competition is likely to arise and risks of escalation are to be taken seriously. One area of possible competition is the exploitation of lunar resources. The Moon’s surface indeed contains valuable resources such as ice, Helium-3, titanium and potentially carbon dioxide, that can be mined to be either used onsite, or brought back to Earth. Helium-3 has even been identified as “one of the greatest potential energy sources of our time”, from which tremendous economic benefits can be made.

Another important factor is the strategic dimension of the southern lunar pole, one of the most promising sites in terms of resources, and where both the Artemis Program and the ILRS project plan to establish a lunar base. A case in point is the ice present in the permanently shaded areas, which can be used to produce oxygen and hydrogen for rocket propulsion. In this context, all actors may have strong incentives to be the first to reach the Moon and build a base at a key location.

Beyond economic benefits, ‘being the first’ to achieve such ambitious plans would significantly strengthen the international status of the actors involved – and of the leading one(s) specifically. In a recent interview with CCTV, Ye Peijian, a top-level space engineer in China, asserted that geopolitical reasons are playing an increasingly important role in driving the Chinese space program. In 2017, he had already stated that:

“The universe is like the ocean: the moon is like the Diaoyu Islands, and Mars is like Scarborough Shoal. If we don’t go now, our descendants will blame us.”, Ye Peijian, 2017.

Within the context of rivalry between the US and China, the latter may want to demonstrate that it is able not only to compete with the US, but also to overtake it in the tech-intensive space realm – while the former wishes to reassert its position as a global leader.

It is also crucial to point out that being the first enables one to set precedence and to contribute to shaping the norms surrounding exploration and exploitation of the Moon. International law regarding the exploitation of space resources being as lacking as it is, pioneers will undoubtedly contribute to shaping international norms.

The importance of being the first may, however, favor the emergence of a ‘zero-sum-game’ mentality, potentially leading to tensions between actors on the Moon and to open conflicts.