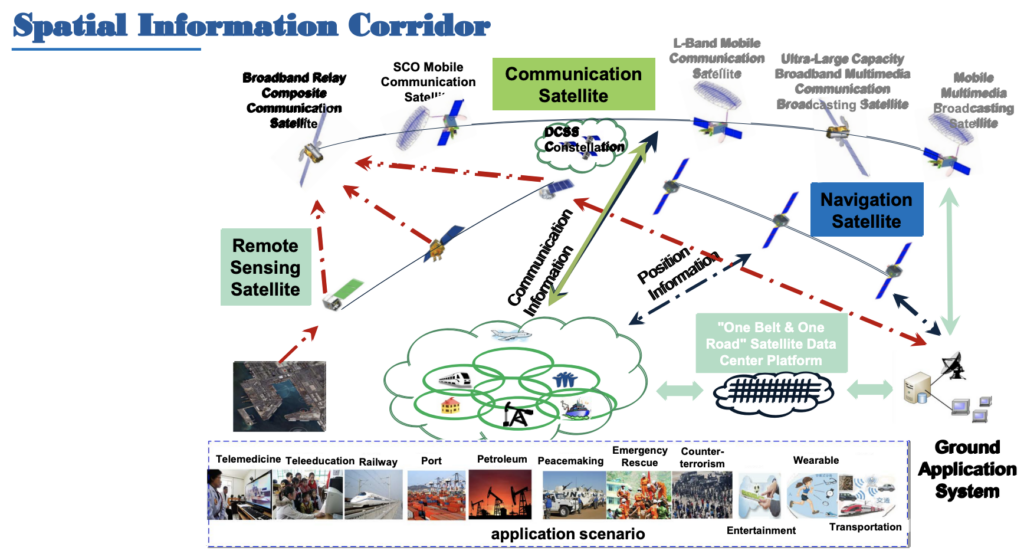

Earlier this month, we saw the First China-Africa BeiDou System Cooperation Forum, held in Beijing on Friday 5 November. The forum was a big one, with representatives from dozens of African nations and a handful of high-level Chinese officials in attendance. While the forum itself saw a limited number of concrete announcements, it was but the latest example of China’s Belt & Road (BRI) Spatial Information Corridor, a series of primarily space projects including BeiDou, global communication satellite constellations, and global EO constellations. While much of the infrastructure in the Spatial Information Corridor will be used by China, there is also clearly an export component to it, as was witnessed at the China-Africa BeiDou Forum a couple of weeks ago.

The forum saw representatives from 48 African countries, including no less than 8 Government Ministers and 8 ambassadors to China. The event called for increased cooperation between China and Africa in developing Beidou applications, a phrase we have heard used before in other regions including Southeast Asia. Typically, this would include developing or implementing terminals to be installed on shipping containers, heavy machinery, and various government infrastructure to provide enhanced navigation services.

Why Does Sub-Saharan Africa Need Chinese Satnav?

In a region like Sub-Saharan Africa, which does not have its own satnav constellation, there are several choices, namely the American Global Positioning System (GPS), European Galileo, Russian GLONASS, or indeed, China’s BeiDou. While each system offers benefits and drawbacks, China is likely the most active of the 4 at encouraging (oftentimes through subsidy, it would seem) other countries to adopt their system. It should also be noted that the systems are not mutually exclusive: many mobile phones are compatible with multiple satnav systems, for instance.

This month’s Forum was hosted at the offices of China Great Wall Industry Corporation, which as we discussed in a previous article, is located in a beautiful former hotel near a quasi-mythical garden. The offices regularly host foreign guests, with CGWIC acting as the primary interface between the traditional Chinese space sector and the outside world.

A variety of high-level Chinese space industry figures gave speeches, including He Yubin, Chairman of the China Satellite Navigation System Committee, Xu Hongliang, Secretary General of the China National Space Administration, and Wu Jianghao, Assistant Minister of Foreign Affairs. African speakers included the Senegalese Minister of Digital Economy and Telecommunications Ndèye Tické Ndiaye Diop, Africa Union Head of Science & Technology Mahama Ouedraogo, and Felix Moloua, the Minister of Planning, Economy, and Cooperation of the Central African Republic (NB: we cannot be 100% sure of the African speaker’s names. Their names were translated into Chinese in the article, and we tried to backtrack by finding people with very similar titles and similar-sounding names).

Among other things, speakers interestingly noted the “Africa 2063” Project, a 50-year plan to create a more developed and equal Africa. We also saw discussion on pretty standard topics, including poverty alleviation, job creation, and China helping Africa using know-how that China has accumulated through the rollout of BeiDou.

A Shifting Strategy Surrounding Chinese Projects Abroad

The forum comes at an important time as China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and to a certain extent the BRI Spatial Information Corridor, are starting to face increasing pressure, or at a minimum, decreasing momentum, as questions about debt sustainability arise, and as the political situation in certain key countries along the BRI deteriorate rapidly (such as Ethiopia, which has been a major beneficiary of Chinese investment).

That being the case, digital projects become even more important, in the sense that in this day and age, it’s probably easier to close the business case for a new 5G (or 3G/4G, as the case may be) network in a developing country than it would be for a railway, airport, or other physical infrastructure. This is also true in the space sector.

In the space sector, China appears to be moving away from selling huge pieces of expensive hardware (like telecommunications satellites costing hundreds of millions of US$) towards selling applications, oftentimes using Chinese-launched hardware. The most obvious example of this would be Beidou, where China has launched a global satnav constellation, and is now encouraging countries to use Beidou-compatible chips and other hardware to develop location-based service applications. More recently, we have seen more Chinese EO companies trying to commercialize their data abroad, and in the future, we will likely see a LEO broadband mega-constellation launched, with broadband services/applications being commercialized across the Belt and Road.

This movement from selling large assets to selling services using Chinese assets may not be a bad thing for the receiving countries. Indeed, in the satellite communications industry, we often refer to “Pridesats”, that is, a satellite built as much for national pride as for practical use (NB: the linked article notes that the original author is no longer with the company. One guess as to who the original author is!).

In short, many countries do not have sufficient satcom needs, or sufficient technical expertise, or at times, sufficient money, to justify buying and operating their own satellite. But, because people like seeing rockets with their flag to up, many countries have still purchased their own satellite, oftentimes only to find them sitting mostly idle for most of their 15 years lifetimes. The alternative—namely leasing satellite capacity from some established satellite operator—is far less sexy, but oftentimes far more sensible. This same logic can be applied to a variety of infrastructure vs. services.

What to Expect in the Future?

Moving forward, we expect to see China continue to roll out digital infrastructure in developing countries, including many along the Belt and Road. As the world increasingly goes digital, and as there are only a couple of countries that can plausibly provide full stack of digital services (namely US, China, and very debatably Europe), we are likely to see a continued digital land grab, whereby China and US companies/governments try to forge digital alliances in third countries, both as a proactive measure for one’s own national interests, and in some cases, as a blocking measure to the other party’s national interests.

While China’s Beidou ties in Africa are still less strong than, for example, Southeast Asia (where Thailand and Cambodia, among others, have received Beidou-related investment), we expect to see more Chinese involvement on the continent in the future. This is especially true in countries where China has significant economic interests. For example, Chinese mining companies do a lot of mineral extraction in Sub-Saharan Africa, much of it in countries that are less stable than China. By helping these countries to digitize, China is likely benefitting them, but they are also likely benefiting their own assets in these countries, or at a minimum, allowing them to be better protected. The phrase “win-win cooperation” gets thrown around far too often, but in this case, it may in fact be applicable.

Ultimately, China is one of only a few countries in the physical world that can conceivably export most, if not all, pieces required to build out a digital world. For a variety of countries that do not have such resources, there will be a choice to be made. While each country’s decision-making process will be different, we can probably be sure of one thing: China is likely to continue the charm offensive with events such as the China-Africa BeiDou Cooperation Forum.

For Further Reading

For a deeper-dive into the BRI Spatial Information Corridor, and its broader counterpart the Digital Silk Road, we recommend a great podcast conversation on the China-Africa Podcast with Jonathan Hillman from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington DC. Hillman spoke with the podcast about his recent book, The Digital Silk Road: China’s Quest to Wire the World and Win the Future. The talk with Hillman not only gives a great overview of what the Digital Silk Road is, but also provides a fascinating comparative reference by discussing how these projects are being received in Washington DC.